The Ancient Celtic Festivals of Ireland: A Seasonal Journey Through Time

Modern celebration of Samhain, showing the continued influence of ancient Celtic traditions Wikipedia

Modern celebration of Samhain, showing the continued influence of ancient Celtic traditions Wikipedia

Introduction: The Sacred Rhythm of Celtic Life

Long before calendars marked our days and smartphones reminded us of appointments, the ancient Celts of Ireland lived by a different clock—one governed by the sun, the moon, and the changing seasons. Their year was not divided into months as we know them, but into eight significant turning points, each marked by a festival that celebrated the cyclical nature of life, death, and rebirth. These Celtic festivals were not merely occasions for merriment, though celebration certainly played a part. They were sacred periods when the veil between worlds thinned, when harvests were gathered or planted, when livestock was brought down from summer pastures or driven out to them, and when communities came together to perform rituals that ensured their survival and prosperity. Today, echoes of these ancient celebrations persist in modern Irish culture and beyond. Halloween, May Day, Midsummer celebrations—all have roots in Celtic festival traditions that stretch back thousands of years. By understanding these celebrations, we gain insight not only into the practical aspects of ancient Celtic life but also into their profound spiritual connection to the natural world. In this exploration of ancient Celtic festivals, we’ll journey through the wheel of the year as the Celts understood it, discovering the rich traditions, powerful symbols, and enduring legacies of these sacred celebrations.The Celtic Calendar: A Different Way to Mark Time

Using Tool

|

Image Search

Celtic wheel of the year calendar

The Celtic Wheel of the Year showing the eight major festivals Wikipedia

The Celtic calendar reflected a profound understanding of natural cycles and astronomical events. Unlike our modern Gregorian calendar, which divides the year into somewhat arbitrary months, the Celtic year was organized around solar and agricultural turning points.

The most important division was between the light half of the year (summer) and the dark half (winter). This primary division was marked by the festivals of Samhain and Bealtaine. The Celtic day was also considered to begin at sunset rather than sunrise, reflecting the belief that darkness preceded light in the cosmic order.

The Celtic Wheel of the Year showing the eight major festivals Wikipedia

The Celtic calendar reflected a profound understanding of natural cycles and astronomical events. Unlike our modern Gregorian calendar, which divides the year into somewhat arbitrary months, the Celtic year was organized around solar and agricultural turning points.

The most important division was between the light half of the year (summer) and the dark half (winter). This primary division was marked by the festivals of Samhain and Bealtaine. The Celtic day was also considered to begin at sunset rather than sunrise, reflecting the belief that darkness preceded light in the cosmic order.

The Four Major Fire Festivals

The Celtic year was anchored by four major fire festivals, each marking a significant seasonal transition:- Samhain (November 1): Marking the beginning of winter and the Celtic New Year

- Imbolc (February 1): Celebrating the first stirrings of spring

- Bealtaine (May 1): Heralding the beginning of summer

- Lughnasadh (August 1): Celebrating the first harvest

The Solar Festivals

In addition to the four fire festivals, the Celts also observed the solstices and equinoxes:- Winter Solstice (around December 21): The longest night of the year

- Spring Equinox (around March 21): When day and night are equal in length

- Summer Solstice (around June 21): The longest day of the year

- Autumn Equinox (around September 21): When day and night are again equal

Samhain: The Celtic New Year

Using Tool

|

Image Search

ancient Samhain celebration Celtic Ireland

Modern recreation of a Samhain fire festival in County Westmeath, Ireland Irish Experience Tours

Samhain (pronounced “SAH-win” or “SOW-in”) marked the Celtic New Year and the beginning of the dark half of the year. Celebrated from sunset on October 31 to sunset on November 1, this festival has evolved into what we now know as Halloween, though many of its original elements have been transformed or lost.

Modern recreation of a Samhain fire festival in County Westmeath, Ireland Irish Experience Tours

Samhain (pronounced “SAH-win” or “SOW-in”) marked the Celtic New Year and the beginning of the dark half of the year. Celebrated from sunset on October 31 to sunset on November 1, this festival has evolved into what we now know as Halloween, though many of its original elements have been transformed or lost.

The Significance of Samhain

Samhain represented a crucial transition in the agricultural cycle. By this time, the harvest was complete, and livestock were either slaughtered for winter meat or brought down from summer pastures. It was a time of preparation for the coming winter—a period of both abundance (from the recent harvest) and anxiety about the cold, dark months ahead. Beyond its practical aspects, Samhain had profound spiritual significance. The Celts believed that during this festival, the boundary between the living world and the Otherworld became thin, allowing spirits of the dead to cross over and visit their living relatives.Samhain Traditions and Rituals

The most iconic element of Samhain was the great bonfire. Communities would extinguish all household fires and gather to light a communal sacred fire, often on hilltops. This fire symbolized the sun’s life-giving power that would return after winter. People would take flames from this central fire to relight their hearth fires, creating a symbolic connection throughout the community. Other significant traditions included:- Feasting with the dead: Places at the table were set for deceased ancestors who might visit during the festival.

- Disguises and costumes: People wore masks and costumes to confuse malevolent spirits who might be abroad during this liminal time—a practice that evolved into modern Halloween costumes.

- Divination practices: The thin veil between worlds made Samhain an ideal time for divination. Young people might peel apples, looking for symbols in the peeled skin that would reveal the name or appearance of their future spouse.

- Offerings: Food and drinks were left outside homes for wandering spirits.

The Otherworldly Dimension

The Celtic concept of the Otherworld was complex. Unlike the Christian heaven and hell that would later influence Irish belief, the Otherworld was a parallel dimension where the dead, the gods, and supernatural beings resided. It wasn’t strictly separate from the living world but existed alongside it, with certain places (like hills, lakes, and caves) and times (like Samhain) serving as access points between the worlds. During Samhain, it was believed that not only could the dead return, but the sidhe (fairy folk) were particularly active and powerful. The tradition of leaving offerings was partly to appease these supernatural entities.From Samhain to Halloween

When Christianity came to Ireland, many Samhain traditions were incorporated into the Christian festival of All Saints’ Day (November 1) and All Souls’ Day (November 2). The evening before All Saints’ Day became known as All Hallows’ Eve, eventually shortened to Halloween. Many Samhain customs persisted under this new religious context. The practice of honoring the dead continued, though now focused on Christian saints and souls in purgatory rather than ancestral spirits. The bonfires, costumes, and feasting traditions also endured, though their meanings were often reinterpreted within a Christian framework.Imbolc: Awakening of Spring

Using Tool

|

Image Search

Imbolc Celtic festival Brigid Ireland

A traditional St. Brigid’s Cross, made from rushes and associated with both the Celtic goddess and Christian saint Wikipedia

Imbolc (pronounced “IM-bulk” or “IM-bolg”), celebrated on February 1, marked the first stirrings of spring in the Celtic world. While winter still held the land in its grip, subtle signs of renewal were becoming visible—lambs being born, the first green shoots emerging, and days gradually lengthening. The name Imbolc likely derives from the Old Irish “i mbolg,” meaning “in the belly,” referring to pregnant ewes carrying lambs that would soon be born.

A traditional St. Brigid’s Cross, made from rushes and associated with both the Celtic goddess and Christian saint Wikipedia

Imbolc (pronounced “IM-bulk” or “IM-bolg”), celebrated on February 1, marked the first stirrings of spring in the Celtic world. While winter still held the land in its grip, subtle signs of renewal were becoming visible—lambs being born, the first green shoots emerging, and days gradually lengthening. The name Imbolc likely derives from the Old Irish “i mbolg,” meaning “in the belly,” referring to pregnant ewes carrying lambs that would soon be born.

Brigid: Goddess and Saint

Central to Imbolc was the goddess Brigid (also spelled Brighid or Bride), a powerful Celtic deity associated with fertility, healing, poetry, and smithcraft. Brigid was a goddess of fire and purification, embodying the returning light and warmth of spring. With the arrival of Christianity in Ireland, rather than disappearing, Brigid underwent a fascinating transformation. She became St. Brigid of Kildare, one of Ireland’s most beloved saints. Many of the attributes of the goddess were transferred to the saint, including her associations with fire, healing, and fertility. This remarkable continuity demonstrates how Celtic traditions often merged with Christian practices rather than being fully displaced by them. St. Brigid’s feast day falls on February 1, directly coinciding with Imbolc.Imbolc Traditions and Rituals

The rituals of Imbolc centered around fire and purification, appropriate for a festival celebrating the returning light. Some key traditions included:- Making Brigid’s crosses: These distinctive crosses, woven from rushes or straw, were created to honor Brigid and to protect homes from fire and evil. They were traditionally placed above doorways and replaced each Imbolc.

- The Brigid’s Bed: Young women would create a doll-like figure of Brigid (called a Brideog) from rushes or corn sheaves, dress it in white clothing, and place it in a basket or “bed” with a white wand made from birch, willow, or other sacred wood. This represented inviting Brigid into the home to bestow blessings.

- Brigid’s Mantle or Cloak: In some communities, a piece of cloth would be left outside overnight on Imbolc Eve for Brigid to bless as she passed by. This “Brigid’s Mantle” was then used for healing throughout the year.

- Weather divination: Imbolc was associated with weather forecasting. According to tradition, if the weather was fair on Imbolc, the second half of winter would be harsh. If the day was stormy, spring would arrive early. This tradition has echoes in the American Groundhog Day, which falls on February 2.

- Hearth fires and candles: As a fire festival, special attention was paid to the hearth. Fires might be extinguished and relit, symbolizing the fresh start of spring. Later Christian traditions incorporated candle blessings on February 2 (Candlemas).

Sacred Sites and Water Sources

Imbolc also had strong associations with sacred wells and springs. Brigid was linked to healing waters, and many holy wells throughout Ireland are still dedicated to her. During Imbolc, people would visit these wells, leaving offerings and performing clockwise circuits while praying for health and blessings. The connection to water reflects the practical importance of reliable water sources as spring approached, but also the symbolic significance of the melting snows and increasing rainfall that would bring life back to the land.Imbolc’s Legacy

While not as widely recognized today as Samhain (Halloween), Imbolc has experienced a revival of interest. In Ireland, St. Brigid’s Day celebrations continue many ancient customs. The traditional craft of making Brigid’s crosses is still practiced, and some families still place a ribbon or cloth outside on the eve of the festival. In recent years, there has been a growing movement to recognize St. Brigid’s Day as a national holiday in Ireland, acknowledging both its Christian significance and its deep roots in pre-Christian Celtic tradition.Bealtaine: Gateway to Summer

Using Tool

|

Image Search

Bealtaine May Day Celtic festival Ireland

Modern Bealtaine Fire Festival at the Hill of Uisneach, the sacred center of Ireland The Hill of Uisneach

Bealtaine (pronounced “BYAL-tah-neh” or “BYAL-tin”), celebrated on May 1, marked the beginning of summer in the Celtic calendar. As the counterpart to Samhain, Bealtaine represented the threshold between the dark half of the year and the light half. It was a time of optimism and abundance, when the world was in full bloom and the promise of summer lay ahead.

The name Bealtaine likely comes from the Old Irish words “bel tene” meaning “bright fire,” reflecting the festival’s association with purifying flames. In modern Irish, “Mí na Bealtaine” is still the name for the month of May.

Modern Bealtaine Fire Festival at the Hill of Uisneach, the sacred center of Ireland The Hill of Uisneach

Bealtaine (pronounced “BYAL-tah-neh” or “BYAL-tin”), celebrated on May 1, marked the beginning of summer in the Celtic calendar. As the counterpart to Samhain, Bealtaine represented the threshold between the dark half of the year and the light half. It was a time of optimism and abundance, when the world was in full bloom and the promise of summer lay ahead.

The name Bealtaine likely comes from the Old Irish words “bel tene” meaning “bright fire,” reflecting the festival’s association with purifying flames. In modern Irish, “Mí na Bealtaine” is still the name for the month of May.

Fire and Fertility

Like other Celtic festivals, Bealtaine centered around fire. Great bonfires were lit on hilltops throughout Ireland, creating a network of flames visible across the landscape. These fires had both practical and spiritual purposes:- They were believed to have protective qualities, guarding communities against disease and misfortune

- Cattle were driven between two fires to purify them and ensure their fertility before being led to summer pastures

- The smoke from Bealtaine fires was thought to have protective properties for crops

- The ashes from the fires were scattered over fields to ensure their fertility

The May Bush and May Flowers

Among the most widespread Bealtaine traditions was the decoration of the May Bush—typically a hawthorn or other flowering bush or small tree. This would be adorned with ribbons, flowers, shells, and sometimes candles or other items. In community celebrations, a central May Bush might be set up in a village square or other gathering place. The hawthorn was particularly associated with Bealtaine. Blooming around this time of year, its white flowers were seen as emblematic of the season. However, there was a strong taboo against bringing hawthorn blossoms inside the home, as this was thought to bring bad luck or illness—possibly related to beliefs about the hawthorn’s associations with the fairy folk. Flowers played a crucial role in Bealtaine celebrations. Yellow flowers like primroses, gorse, and marsh marigolds were particularly associated with the festival, perhaps because their color echoed the sun and fire. These flowers would be used to decorate homes and farm buildings, and sometimes strewn across thresholds for protection.The May Queen and May King

In some regions, Bealtaine celebrations included the crowning of a May Queen and sometimes a May King. These figures represented the fertility and abundance of the season. The May Queen, adorned with flowers and ribbons, led processions through villages or around fields, symbolically bringing the blessings of summer to the community. This tradition has parallels throughout Europe, where May Day celebrations often featured similar symbolic figures representing the fertility of the season.Protection Against the Otherworld

Like Samhain, Bealtaine was considered a time when the veil between worlds was thin, allowing the sidhe (fairy folk) and other supernatural beings easier access to the human world. While this liminal quality made Bealtaine powerful for divination and magic, it also represented potential danger. Many Bealtaine traditions focused on protection:- Yellow flowers placed on doorsteps and windowsills to protect against fairy mischief

- Special prayers or charms recited at dawn on May Day

- Rowan branches hung over doors and windows for protection

- The first water drawn from wells on May morning was thought to have special properties, and people would wash their faces in it for luck and protection

Bealtaine in Modern Times

Many aspects of Bealtaine have survived into modern May Day celebrations, though often without their original context. Maypole dancing, still practiced in parts of Ireland and Britain, has roots in Bealtaine traditions, with the pole representing fertility and the intertwining ribbons symbolizing the union of masculine and feminine energies. In Ireland, there has been a revival of interest in traditional Bealtaine celebrations. The Hill of Uisneach in County Westmeath, considered the sacred center of Ireland in Celtic tradition, now hosts an annual Bealtaine Fire Festival that draws thousands of participants, reigniting the ancient tradition of lighting the summer fire.Lughnasadh: First Harvest

Using Tool

|

Image Search

Lughnasadh harvest festival Celtic Ireland

A depiction of harvesting activities associated with Lughnasadh Historic Mysteries

Lughnasadh (pronounced “LOO-nah-sah” or “LOO-na-sa”), celebrated on August 1, marked the beginning of the harvest season. Named for the Celtic god Lugh, this festival combined thanksgiving for the first fruits with competitive games and gatherings that strengthened community bonds before the intensive work of the main harvest.

A depiction of harvesting activities associated with Lughnasadh Historic Mysteries

Lughnasadh (pronounced “LOO-nah-sah” or “LOO-na-sa”), celebrated on August 1, marked the beginning of the harvest season. Named for the Celtic god Lugh, this festival combined thanksgiving for the first fruits with competitive games and gatherings that strengthened community bonds before the intensive work of the main harvest.

Lugh: The Many-Skilled God

Lugh was one of the most important deities in the Celtic pantheon. Known as “Lugh Lámhfhada” (Lugh of the Long Arm), he was a god of light, crafts, and various skills. According to Irish mythology, Lugh was the grandson of Balor of the Evil Eye, a fearsome Fomorian giant whom Lugh eventually slew, thereby securing the prosperity of Ireland. What made Lugh unique among Celtic gods was his mastery of multiple skills. He was said to be a warrior, a craftsman, a poet, a harpist, a healer, and more—earning him the epithet “Samildánach” (equally skilled in many arts). This multi-talented nature made him particularly significant for a festival that brought together various aspects of community life.The Origins of Lughnasadh

According to Irish mythology, Lughnasadh was established by Lugh himself as a funeral feast and games to honor his foster mother, Tailtiu, who died of exhaustion after clearing the plains of Ireland for agriculture. The festival thus had elements of both mourning and celebration—honoring sacrifice while also celebrating the fruits it made possible. The most famous of these celebrations was the Tailteann Games, held at Teltown in County Meath. These games included athletic competitions, horse races, storytelling contests, and trading. They were, in some ways, Ireland’s equivalent to the ancient Olympic Games, bringing together communities from across the island.Harvest Traditions

As a harvest festival, Lughnasadh centered around the first fruits of the season, particularly grain. Key traditions included:- First grain ceremonies: The first sheaf of grain would be ceremonially cut, often by the community leader or a specially selected harvester. This grain might be ground into flour and baked into a special “Lughnasadh bread” shared among the community.

- Corn dollies: Using the last sheaf from the previous year’s harvest (kept through the winter) and the first sheaf of the new harvest, people created corn dollies—figures woven from straw that embodied the spirit of the harvest. These might be kept until the following year to ensure continued abundance.

- Blueberry picking: In many parts of Ireland, Lughnasadh coincided with the ripening of bilberries (similar to blueberries). Gathering these berries was a traditional activity, often done by young people who would then present them to their sweethearts.

- Hilltop gatherings: Communities would gather on hilltops for feasting and celebration, sometimes overnight. These gatherings combined practical purposes (trading, arranging marriages) with religious observances and entertainment.

Trial Marriages and Handfasting

An intriguing aspect of Lughnasadh was the tradition of “trial marriages” or handfasting. At the Lughnasadh gatherings, couples could enter into a temporary marriage agreement that lasted until the next Lughnasadh. If, after a year and a day, the couple wished to part ways, they could do so without stigma. If they wished to continue the relationship, a more permanent arrangement would be made. These trial marriages were practical in a society where compatibility and fertility were crucial for survival. They allowed couples to determine if they were well-matched before making a permanent commitment.Lughnasadh in Christian Times

With the coming of Christianity, Lughnasadh was incorporated into the Christian calendar as Lammas (from “loaf-mass”), a festival where the first loaves made from the new harvest were blessed in church. Many of the games and gatherings continued, now often associated with saints’ days falling around the same time. In Ireland, Lughnasadh became associated with pilgrimages to holy wells and mountains. The tradition of climbing Croagh Patrick in County Mayo on the last Sunday in July (known as “Reek Sunday”) likely evolved from a pre-Christian Lughnasadh ritual, though it is now associated with St. Patrick.Modern Observances

While not as widely recognized as some other Celtic festivals, Lughnasadh has seen a revival of interest in recent decades. In some parts of Ireland, traditional Lughnasadh fairs have been revived, featuring local foods, crafts, music, and competitions. The town of Killorglin in County Kerry preserves elements of Lughnasadh in its annual Puck Fair, held in August. During this three-day festival, a wild goat is captured from the mountains and crowned “King Puck,” presiding over the fair from an elevated platform before being released back to the mountains. While the exact origins of this tradition are debated, many scholars see connections to Lughnasadh celebrations.Solar Festivals in Celtic Tradition

Using Tool

|

Image Search

Celtic solstice celebration Newgrange Ireland

Winter solstice sunlight illuminating the inner chamber of Newgrange, a 5,200-year-old passage tomb in Ireland Newgrange

While the four fire festivals (Samhain, Imbolc, Bealtaine, and Lughnasadh) are often emphasized in discussions of Celtic festivals, the solstices and equinoxes—marking the extremes and balances of light and darkness throughout the year—were also significant to the ancient Celts.

Evidence for the importance of these solar events comes not just from historical sources but from the alignment of ancient monuments. The most famous of these is Newgrange, a 5,200-year-old passage tomb in Ireland’s Boyne Valley, precisely aligned so that the rising sun on the winter solstice illuminates its inner chamber.

Winter solstice sunlight illuminating the inner chamber of Newgrange, a 5,200-year-old passage tomb in Ireland Newgrange

While the four fire festivals (Samhain, Imbolc, Bealtaine, and Lughnasadh) are often emphasized in discussions of Celtic festivals, the solstices and equinoxes—marking the extremes and balances of light and darkness throughout the year—were also significant to the ancient Celts.

Evidence for the importance of these solar events comes not just from historical sources but from the alignment of ancient monuments. The most famous of these is Newgrange, a 5,200-year-old passage tomb in Ireland’s Boyne Valley, precisely aligned so that the rising sun on the winter solstice illuminates its inner chamber.

Winter Solstice: The Return of Light

The winter solstice, occurring around December 21, marks the shortest day and longest night of the year. After this point, daylight begins to increase again—a crucial turning point in agricultural societies dependent on the sun’s energy. Archaeological evidence suggests this was a significant event for the people who built Newgrange and similar monuments. The precise alignment of the passage tomb, allowing sunlight to penetrate the normally dark inner chamber for just a few minutes around the solstice, demonstrates extraordinary astronomical knowledge and the importance attached to this solar event. In Celtic tradition, the winter solstice represented:- The rebirth of the sun

- The triumph of light over darkness

- A time for reflection as the old year ebbed

- A celebration of surviving the darkest point of the year

Summer Solstice: The Height of Light

The summer solstice, around June 21, marks the longest day and shortest night of the year. For agricultural communities, this abundance of light represented the height of the sun’s power and the flourishing of crops and livestock. Celtic summer solstice traditions included:- Gathering of medicinal herbs, which were believed to be at their most potent on this day

- Lighting of bonfires on hilltops, echoing the sun’s power

- All-night revelry and feasting

- Rituals to protect crops during the coming harvest season

Spring and Autumn Equinoxes: Balance of Light and Dark

The spring (around March 21) and autumn (around September 21) equinoxes mark the points when day and night are of equal length. These moments of perfect balance between light and darkness had their own significance in Celtic tradition. The spring equinox represented:- The definitive triumph of light over winter’s darkness

- A time of balance before the surge of summer growth

- The renewal of life and fertility

- The balance point before darkness began to dominate

- The completion of the main harvest

- Preparation for the coming winter

- A time to give thanks for the year’s abundance

The Living Legacy: Celtic Festivals in Modern Ireland

Using Tool

|

Image Search

modern Celtic festival celebration Ireland

Modern celebration of the Bealtaine Fire Festival at the Hill of Uisneach Irish Experience Tours

While the ancient Celtic festivals have evolved over the centuries, many of their elements persist in modern Irish culture, sometimes in surprising ways. This living legacy demonstrates the resilience of cultural traditions and their ability to adapt to changing circumstances.

Modern celebration of the Bealtaine Fire Festival at the Hill of Uisneach Irish Experience Tours

While the ancient Celtic festivals have evolved over the centuries, many of their elements persist in modern Irish culture, sometimes in surprising ways. This living legacy demonstrates the resilience of cultural traditions and their ability to adapt to changing circumstances.

Modern Samhain/Halloween

Of all the Celtic festivals, Samhain has maintained the strongest presence in contemporary culture through its evolution into Halloween. In modern Ireland, Halloween continues many ancient Samhain traditions:- Bonfires are still lit in many communities

- Costume-wearing continues the ancient practice of disguise

- Jack-o’-lanterns, originally carved from turnips in Ireland before pumpkins became the norm in America, echo the old practice of carrying lights to ward off spirits

- Divination games like apple-bobbing have roots in Samhain traditions

- Trick-or-treating may have evolved from the ancient practice of going door-to-door in disguise, receiving offerings meant for the ancestors

St. Brigid’s Day/Imbolc Revival

February 1st, the traditional date of Imbolc, is now celebrated in Ireland as St. Brigid’s Day. In 2023, it became Ireland’s newest public holiday, the first named after a female figure. This official recognition represents a significant revival of interest in this ancient festival. Modern St. Brigid’s Day celebrations include:- Cross-making workshops teaching the traditional craft of creating Brigid’s crosses

- Well visitations to the many holy wells dedicated to St. Brigid throughout Ireland

- Lighting ceremonies reflecting the fire aspect of both the goddess and saint

- Women’s gatherings celebrating female creativity and leadership

- Food festivals featuring traditional early spring foods

Bealtaine Festival for Older People

In a fascinating adaptation of an ancient tradition, Ireland now hosts an annual Bealtaine Festival throughout the month of May—but with a unique focus on creativity in older age. This nationwide festival celebrates creativity as people age, with hundreds of events across Ireland. While different in purpose from the ancient fertility festival, this modern Bealtaine maintains the spirit of celebration, renewal, and community that characterized the original. It represents how traditions can evolve while maintaining their essential character. Meanwhile, more traditional Bealtaine celebrations are being revived as well:- The Uisneach Bealtaine Fire Festival at the Hill of Uisneach has been revived, drawing thousands to witness the lighting of the sacred fire

- May Bushes are still decorated in some communities

- Dawn ceremonies welcoming the first day of summer take place at various ancient sites

Lughnasadh/Puck Fair

Elements of Lughnasadh survive in several modern Irish festivals:- Puck Fair in Killorglin, County Kerry, held in August, features the crowning of a wild mountain goat as “King Puck”—a tradition with potential roots in pre-Christian harvest ceremonies

- Garland Sunday (the last Sunday in July) continues the tradition of visiting holy wells and heights

- Croagh Patrick pilgrimage on “Reek Sunday” (the last Sunday in July) involves climbing the sacred mountain in County Mayo

- Fraughan (bilberry) Sunday maintains the tradition of bilberry picking associated with Lughnasadh

Solstice Celebrations

The winter solstice at Newgrange has become one of Ireland’s most significant cultural events. Each year, thousands apply for the lottery to be among the few allowed inside the chamber to witness the solstice sunrise illumination. Even those who don’t gain entry often gather outside to celebrate this ancient astronomical phenomenon. Summer solstice celebrations have also seen a revival, with gatherings at various stone circles and other ancient sites throughout Ireland to mark the longest day.Celtic Festivals Beyond Ireland

Using Tool

|

Image Search

Celtic festival Scotland Wales Brittany

Musicians at the Festival Interceltique de Lorient in Brittany, France, a modern celebration of Celtic culture Wikipedia

While this guide has focused on Irish Celtic festivals, it’s worth noting that similar celebrations existed—and continue to exist—throughout the Celtic world, including Scotland, Wales, Cornwall, Brittany, and parts of Spain. These regions shared a common Celtic heritage, though with regional variations in traditions and practices.

Musicians at the Festival Interceltique de Lorient in Brittany, France, a modern celebration of Celtic culture Wikipedia

While this guide has focused on Irish Celtic festivals, it’s worth noting that similar celebrations existed—and continue to exist—throughout the Celtic world, including Scotland, Wales, Cornwall, Brittany, and parts of Spain. These regions shared a common Celtic heritage, though with regional variations in traditions and practices.

Scotland’s Celtic Festivals

Scotland shares many festival traditions with Ireland, though often with distinct local characteristics:- Beltane (Bealtaine) is still celebrated with the famous Beltane Fire Festival in Edinburgh, a modern revival that draws thousands of participants

- Samhuinn (Samhain) is marked by fire processions in Edinburgh and other cities

- Up Helly Aa in the Shetland Islands, while influenced by Norse rather than Celtic traditions, shares the fire festival characteristics of other Celtic celebrations

Welsh Traditions

In Wales, Celtic festival traditions include:- Gŵyl Fair y Canhwyllau (Mary’s Festival of the Candles), the Welsh version of Imbolc/Candlemas

- Calan Mai (the first day of May), equivalent to Bealtaine, with traditions of decorating May bushes

- Calan Gaeaf (the first day of winter), the Welsh counterpart to Samhain

Brittany’s Celtic Heritage

Brittany in northwestern France maintains strong Celtic connections, with festivals including:- Gouel Beloal, the Breton version of Bealtaine

- Festival Interceltique de Lorient, a modern celebration that brings together Celtic cultures from across Europe

- Samhain celebrations that maintain ancient traditions of honoring the dead

Modern Pan-Celtic Festivals

Today, there are numerous festivals celebrating the shared heritage of the Celtic nations, including:- Pan Celtic Festival, rotating between different Celtic nations

- Celtic Connections in Glasgow, Scotland

- Festival Interceltique in Lorient, Brittany

The Spiritual Dimension of Celtic Festivals

Using Tool

|

Image Search

ancient Celtic religious ceremony druid

19th-century illustration depicting druids harvesting mistletoe during a sacred ceremony Wikipedia

At their core, Celtic festivals were not merely social gatherings or agricultural markers but deeply spiritual events that reflected the Celts’ understanding of the cosmos and their place within it. Though we have limited direct sources about Celtic religious practices (the druids, their priestly class, preferred oral transmission of knowledge to written records), the spiritual dimensions of these festivals can be discerned from archaeological evidence, later written accounts, and surviving traditions.

19th-century illustration depicting druids harvesting mistletoe during a sacred ceremony Wikipedia

At their core, Celtic festivals were not merely social gatherings or agricultural markers but deeply spiritual events that reflected the Celts’ understanding of the cosmos and their place within it. Though we have limited direct sources about Celtic religious practices (the druids, their priestly class, preferred oral transmission of knowledge to written records), the spiritual dimensions of these festivals can be discerned from archaeological evidence, later written accounts, and surviving traditions.

The Sacred Calendar

The Celtic festival calendar reflects a spirituality deeply rooted in natural cycles. By aligning their major celebrations with solar events and agricultural turning points, the Celts demonstrated their understanding of the interconnectedness of all life and the importance of maintaining harmony with natural rhythms. The division of the year into the dark and light halves (beginning with Samhain and Bealtaine respectively) reflected a dualistic worldview that acknowledged the necessity of both light and darkness, life and death, in the cosmic order. Rather than seeing these as opposing forces, the Celts viewed them as complementary aspects of a unified whole.The Role of Druids

The druids, the learned class in Celtic society, played a central role in festival celebrations. These figures combined the roles of priest, judge, healer, and keeper of tradition. They possessed extensive knowledge of the natural world, astronomy, and religious practices. During festivals, druids likely led ceremonies that included:- Ritual fires and their lighting in specific ways

- Sacrifices and offerings to deities and ancestors

- Divination to glimpse the future

- Blessings for protection and prosperity

- Recitation of myths and legends relevant to the particular festival

The Thin Veil: Celtic Concepts of the Otherworld

Central to Celtic spirituality was the concept of the Otherworld—not a distant realm but a dimension that existed alongside the physical world, separated only by a thin veil that could be penetrated at certain times and places. The major festivals, particularly Samhain and Bealtaine, were considered times when this veil was at its thinnest. This concept reflects the Celtic understanding of reality as layered and interconnected. The physical and spiritual worlds were not sharply divided but existed in constant interaction. Sacred sites like hills, wells, and groves were locations where the boundaries between worlds were particularly permeable, which is why many festival celebrations took place at these locations.Animistic Worldview

The Celtic worldview was fundamentally animistic—recognizing spirit or divinity in natural features, animals, and phenomena. Their festivals honored this ensouled landscape, acknowledging the spirits of the land, waters, and forests as active participants in the ceremony. This animistic perspective is evident in practices like:- Leaving offerings at sacred wells and trees

- Speaking directly to natural features in ritual contexts

- Creating representations of nature spirits in art and ritual objects

- Observing taboos related to certain natural features or creatures

Continuity and Transformation

One of the most fascinating aspects of Celtic spirituality is how it adapted rather than disappeared with the coming of Christianity. Elements of the old festivals were incorporated into Christian observances, creating a distinctive Celtic Christianity that maintained connections to the pre-Christian past. Saints’ days replaced deity celebrations, holy wells once dedicated to goddesses became associated with the Virgin Mary or female saints, and seasonal observances continued under new names and frameworks. This syncretic approach allowed for the preservation of many ancient spiritual practices while accommodating the new religion.Recreating Celtic Festival Traditions Today

Using Tool

|

Image Search

modern Celtic festival celebration home ritual

A modern home altar arrangement for celebrating Celtic festivals Mythology Vault

You don’t need to be in Ireland or have Celtic ancestry to incorporate elements of these ancient festivals into your life. Here are some thoughtful ways to connect with these traditions in contemporary contexts.

A modern home altar arrangement for celebrating Celtic festivals Mythology Vault

You don’t need to be in Ireland or have Celtic ancestry to incorporate elements of these ancient festivals into your life. Here are some thoughtful ways to connect with these traditions in contemporary contexts.

Samhain/Halloween (Late October/Early November)

Modern ways to honor the spirit of Samhain include:- Create an ancestor altar with photos, mementos, and small offerings to honor your family lineage

- Host a feast with traditional seasonal foods, leaving a place set for absent loved ones

- Tell stories about family members who have passed on, keeping their memory alive

- Spend time in reflection, journaling about the past year and setting intentions for the coming one

- Perform divination using tarot cards, rune stones, or other methods, taking advantage of the liminal energy of the season

Imbolc/St. Brigid’s Day (Early February)

To celebrate the first stirrings of spring:- Learn to make a Brigid’s cross from rushes or straw, a simple craft with deep meaning

- Light candles throughout your home to welcome the returning light

- Start seeds indoors for spring planting, connecting to the agricultural roots of the festival

- Create a Brigid’s bed or simple altar with early spring flowers and symbols of renewal

- Clean and purify your living space, embracing the cleansing aspect of this festival

Bealtaine/May Day (Early May)

Celebrate the beginning of summer with:- Create a May bush by decorating a small branch with ribbons, flowers, and small trinkets

- Gather the morning dew on May 1st, traditionally believed to have healing properties

- Light a small fire (safely!) or work with candle flame to represent the protective fires of Bealtaine

- Decorate with yellow flowers like primroses and marigolds, traditional Bealtaine blooms

- Spend time in nature, appreciating the abundance of late spring and the promise of summer

Lughnasadh/Lammas (Early August)

Honor the first harvest with:- Bake bread from scratch, ideally using locally grown grain if available

- Create a corn dolly or simple grain weaving from straw

- Host a gathering with games, competitions, or sharing of skills, honoring Lugh’s multi-talented nature

- Visit a local farmers’ market to appreciate the seasonal harvest

- Pick berries or other seasonal fruits, connecting to the traditional bilberry gathering

For All Celtic Festivals

Some practices that can enhance any seasonal celebration:- Research local seasonal changes in your area, adapting Celtic traditions to your local ecology

- Learn traditional songs associated with the festivals to incorporate music into your celebrations

- Create a seasonal altar with symbols and natural items representing the particular festival

- Practice mindfulness about seasonal transitions, taking time to notice subtle changes in your environment

- Connect with community through shared meals, rituals, or celebrations that honor the season

Respecting Cultural Context

When adopting elements of Celtic festival traditions, it’s important to approach them with respect for their cultural origins. Rather than appropriating these practices, consider how they might:- Connect you more deeply to the natural cycles in your own environment

- Help you mark the passage of time in meaningful ways

- Provide opportunities for creativity and community building

- Offer space for reflection and intention-setting

Conclusion: The Timeless Relevance of Celtic Festivals

Using Tool

|

Image Search

Celtic seasonal wheel ancient modern ireland

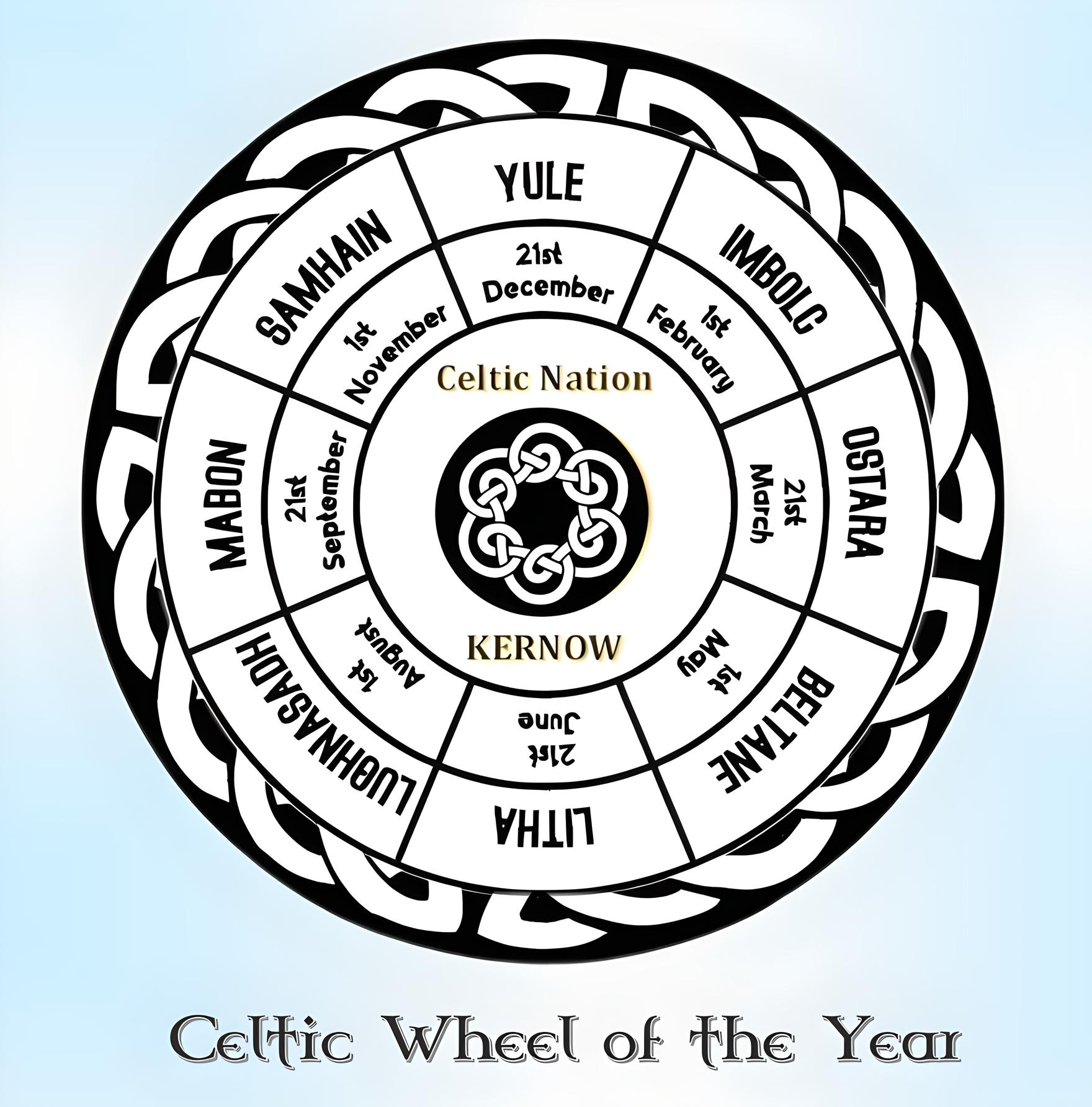

The Celtic Wheel of the Year showing the eight major festivals and their seasonal correspondences Celtic Nation Kernow

The ancient Celtic festivals of Ireland offer more than just a glimpse into historical practices or colorful folklore. They represent a profound way of understanding our relationship with time, nature, and community that remains surprisingly relevant in our modern world.

The Celtic Wheel of the Year showing the eight major festivals and their seasonal correspondences Celtic Nation Kernow

The ancient Celtic festivals of Ireland offer more than just a glimpse into historical practices or colorful folklore. They represent a profound way of understanding our relationship with time, nature, and community that remains surprisingly relevant in our modern world.

Reconnecting with Natural Cycles

In an age of artificial light, climate control, and digital distraction, many people feel disconnected from the natural rhythms that guided human life for millennia. The Celtic festival calendar, with its careful attention to seasonal transitions and cosmic events, offers a framework for reconnecting with these natural cycles. By observing the solstices, equinoxes, and cross-quarter days that mark the Celtic year, we can develop greater awareness of subtle seasonal changes, the movements of the sun and moon, and the cyclical patterns that continue to influence our lives, even in urban environments.Finding Meaning in Transitions

The Celtic festivals mark significant transitions—between seasons, between light and dark, between abundance and scarcity. They acknowledge that change is constant and provide ritual containers for processing these transitions. In our rapidly changing world, having ways to meaningfully mark transitions becomes increasingly important. Whether celebrating personal milestones or navigating collective challenges, the structure offered by seasonal observances can provide stability and meaning amidst change.Building Community in a Fragmented World

The Celtic festivals were fundamentally communal celebrations, bringing people together for shared purposes—whether honoring ancestors, celebrating harvests, or welcoming spring. In our increasingly isolated and individualistic society, these traditions remind us of the importance of gathering, sharing food, telling stories, and maintaining cultural continuity. By reviving and adapting festival traditions, we create opportunities for meaningful connection that transcend the superficial interactions that often characterize modern life.Balancing Past and Future

The Celtic approach to festivals beautifully balanced reverence for tradition with adaptation to changing circumstances. As Christianity arrived in Ireland, festival practices evolved, incorporating new elements while maintaining core celebrations and values. This adaptive approach offers a model for how we might honor cultural heritage while acknowledging the need for evolution. Rather than rigidly preserving traditions or discarding them entirely, we can find the living essence at their core and allow it to take new forms appropriate to our time.The Continuing Journey of the Celtic Year

The Wheel of the Year continues to turn, just as it did for our ancestors. The sun still reaches its zenith at midsummer and its nadir at midwinter. The first flowers still push through frozen ground in early spring, and the harvests still come in during late summer and autumn. By reconnecting with these cyclical patterns through the framework of Celtic festivals, we participate in a tradition that stretches back thousands of years while remaining vibrantly alive today. Whether you have Celtic ancestry or simply appreciate the wisdom embedded in these ancient celebrations, the festivals offer a way to live more mindfully, more connected to nature’s rhythms, and more aware of the sacred dimensions of everyday life. In a world often characterized by disconnection and acceleration, the Celtic festival tradition invites us to slow down, pay attention, and recognize ourselves as part of something larger—a continuing story told through the changing seasons and the eternal dance of darkness and light.